"ALFRED WOLFSOHN alias AMADEUS

DABERLOHN"

The Man and his Ideas

(This lecture was given with

my power point images. Many of these images, you can find on the

Alfred Wolfsohn photo section of this website. I have left in references

to Charlotte’s paintings using the numbers of the Museum’s

DVD. P.Silber)

I would like to begin by thanking

several people who have made it possible for us to be here today: first,

thank you to Joel Cahen, the Museum Director, for his

kind invitation for me to give this lecture; then to Paul Silber, keeper

of the Archives of the Roy Hart Theatre in Malerargues, France, who has

prepared and organised all the images that are used, and finally, thank

you all for being here. I hope you will find it an interesting and valuable

experience.

Between 1940 and 1942 Charlotte

Salomon created over 1300 paintings of which 769 are Life?

or Theatre?, her autobiography conceived as a play with music.

Of these 769 paintings over 370 of them relate to Amadeus Daberlohn or

a man named Alfred Wolfsohn. She entitles this as “The Main Section”,

and portrays Amadeus Daberlohn, hands behind back, walking slowly into

a room to ask for a work permit, but to the tune of the Toreador song

from Carmen! She then adds “and now our play begins”.

The paintings in the exhibition

here are known as the rejected, disapproved or reverse side of Charlotte

Salomon’s Life? or Theatre? I don’t know if any of you have

seen the complete exhibition but the museum has a most remarkable CD Rom

of all her work, with an interesting explanatory post-script written by

Charlotte.

Just to remind you of her story (Charlotte self portrait ): She was the

daughter of Professor Albert Salomon and Francisca Grunwald. Unknown to

Charlotte, her mother Francisca committed suicide when Charlotte was eight

years old, but Lotte was told that her mother died of influenza. She also

knew nothing about another five members of her maternal family who had

also committed suicide.

Her mother, who was acutely depressed, (painting 4175) used to speak to

her about heaven and how she longed to be there. She made a pact with

Lotte that if she got there she would write letters to her which she would

leave on her windowsill. She died. The letters never arrived. Lotte was

lonely and desolate. Her father later married Paula Lindberg, famous singer,

with whom Lotte developed a strong love/hate relationship. This is evident

throughout Life? or Theatre?. (4248) Here she portrays them as “lovers

again” after having had a disagreement.

She also portrays Paulinka’s lack of belief in her art. Here (4339)

Paulinka says to Lotte’s father “frankly I don’t understand

how you can spend all that money. After all she has no talent for drawing.

Everyone says so”. However, she went to art college.

During this time, the Nazi regime, Alfred Wolfsohn, a singing teacher,

was unable to work as he had no work permit. He was advised to contact

Paula Lindberg-Salomon who then employed him as her singing teacher. She

eventually got him a teaching permit and planned to send pupils to him.

He became a friend of the family and soon realised that Lotte was a complicated

girl who had no faith in herself or her art. Knowing the family suicide

history, he became very concerned about her unhappy nature and tried to

help her by talking with her about her art and her self esteem.

In 1939 Lotte was sent to stay with her Grandparents in the South of France,

where everyone felt she would be safe. Some time after her arrival her

grandmother tried to hang herself. Lotte saved her. Her grandfather, in

the most cruel manner, ruthlessly told Lotte the full story of all the

suicides. She was devastated – but she decided to try to help her

grandmother by encouraging her to do something creative as Daberlohn had

encouraged her.

This eventually failed and her grandmother finally threw herself out of

the window (4900 reverse side). Here Lotte sadly repeats “May you

never forget that I believe in you”. This was something Wolfsohn

often said to her, particularly at the moment in which she set off for

the South of France, actually at the railway station.

At this time the war was getting

closer, she and her grandfather were interned in a prison camp for a short

period and released because of his age, but her grandfather became more

and more difficult, often making sexual innuendos to her. Lotte became

more and more lonely and depressed until – quote: “she found

herself facing the question of whether to commit suicide or to do something

wildly eccentric… and …the memory of her fervid early love

came back to her”.

She remembered Daberlohn saying.

“one has to go into oneself, into ones childhood – to be able

to go out of oneself.” …..“And with dream awakened eyes

she saw all the beauty around her, saw the sea, felt the sun, and knew:

that she had to vanish for a while from the human plane and make every

sacrifice in order to create her world anew out of the depths. And from

that came: Life? or Theatre?” (4925)

I met Alfred Wolfsohn in 1947. He was my singing teacher

for 15 years, and for the last five years of his life I was very close

to him as I helped to nurse and look after him when he was ill with tuberculosis.

I did this together with his distant cousin and my greatest friend Marita

Günther. During this time I got to know him as a friend, a father

figure, a unique psychologist/philosopher who never stopped teaching.

He was born in Berlin on the 23rd September 1896, into

a non orthodox Jewish family. His father died of tuberculosis when Alfred

was ten years old and he remained devoted to his mother and older sister.

He was educated at quite a famous school in Berlin and became extremely

well read in all subjects, from literature to mysticism - but music was

his love. He played the piano, violin and viola. However he started to

study Law at University and there he had a great friend who had also been

school with him, who introduced him to the love of art. So music and art

became part of his life.

In 1914, when he was 18 year old, he was conscripted

for the army. He fought on the Russian front and then on the French. Finally

in one fearsome battle, while he was crawling knee deep through the mud

he heard the screams of a comrade crying for help. He desperately wanted

to go to him but he felt he had to save himself - so he crawled on, collapsed

and awoke under a pile of corpses. He was believed to be dead. He crawled

out and he felt he was dead. He did not know how to go on living. He was

sent to a psychiatric hospital but they could not help. The personal horrors

of that war left him mentally and emotionally traumatised.

It was suggested finally that he should go to Italy to recuperate. There

he became absorbed in the art of that country and from then onwards the

artist and his work became an ongoing study. He wanted to understand and

analyse the source of each artistic creation. He never considered the

artistic or monetary value of a work of art, but he was deeply involved

with the content and its connection with its creator.

So the art and music of Italy finally revived him and

when he returned to Germany he knew he wanted to be a singer. He had a

good baritone voice before the war, so he started to have singing lessons

- but his voice did not improve. He knew that the fault lay not with his

teachers but with himself, it was his problem. He had lost his voice and

he knew the loss was connected with his damaged soul or psyche. If he

could heal himself he would heal his voice.

The war had caused him to suffer from two major traumas:

1. The loss of his God. If God exists, why does he allow

this to happen - a question people have asked through the millennium

2. An overwhelming sense of guilt for not having gone

to the help of the injured comrade.

The attempt to solve these traumas lead to the development of his ideas

and the founding of his whole philosophy:

To understand God he needed to

understand the human being on the deepest level - and to understand his

own soul. To solve his guilt he was driven to help others, in fact he

says: quote “all my work is bound up with the need to help other

people, almost to an idiotic degree”. He would refer to this as

his Saviour Complex or his identification with Saviour type.

So in order to understand his own voice problems he started to examine

himself and the human voice. He thought of the voice of a baby.

The baby doesn’t cry, his voice cries out of him. How can these

delicate vocal cords produce such a sound? Why does it change, why does

it become inhibited and cramped as the child grows? He thought of the

uninhibited, terrifying screams of the dying soldiers, like the baby,

often shrieking for their mothers. He thought of an early childhood memory

of his mother singing a song to him of St Peter and the Angel - she used

a deep voice for St Peter and a high one for the angel. He had been impressed

by this even as a child.

He believed that the human

voice is the first and greatest means of communication between

people. If the human psyche is disturbed, inhibited or unable to allow

itself free expression, the voice becomes cramped, held back, complaining

or harsh.

He was impressed by Knut Hamson, the Norwegian novelist in his book Mysteries,

where he speaks about the ‘’Mystery behind the voice”.

You do only have to listen to people speaking to realise exactly what

Wolfsohn is saying.

Wolfsohn also believed that in each human being there are male

and female elements, elements often unexpressed or denied. Although

the voice is affected by puberty, the gender difference, at that time,

was made worse by the demands of society - men were men and women were

women. Any gender over-lap was considered strange. Certainly the POP music

world of today has given permission for the intermingling of vocal gender…POP

males with high voices…young females in England , e.g. weather reporters,

with high nasal sharp voices which unconsciously say, “I have strong

qualities, like a man.”

He was excited when on two occasions he actually heard the voices of his

imagination: first the Russian bass Chaliapine with his

rich deep baritone. He had no fear of expressing ugly, rasping sounds

if the aria required it; and then the Don Kosaken Choir,

an all male choir from white Russia who escaped at the time of the Revolution

– they sang from the deepest, deepest bass into the highest, beautiful

soprano without a break.

At that time too Carl Jung was also writing about the

anima and animus figures in each person, the anima in the man and the

animus in the female. Wolfsohn believed that the integrated human being

should be able to accept these different sides and, by freeing the psychological

inhibitions that limit vocal expression, express the anima and animus

in the voice. Finally any voice should be able to approach the range found

in the traditional bass, baritone, contralto and soprano voices –

and Wolfsohn’s pupils in London eventually proved that this is possible.

(Jill recording) five arias from the magic flute, sung by the same female

singer in the exact key in which they were written for soprano, contralto,

tenor, coloratura and bass. Taken from a audio disc entitled “Alfred

Wolfsohn, the Man and His Musical Ideas”, available from Paul

Silber

So to return to Berlin (1931 picture) in the 1930s he started to work

with people whose voices were deteriorating or people who wanted to sing

but felt they couldn’t do so. Added to this he had to work to support

his ailing mother: he played the piano for silent films, worked in a bank

and helped children who had difficulties with maths.

Every one asks about his method

of teaching, there was no method. He would ask you to

sing a sound, to place it higher in the head or lower in the chest or

body. He would then lead the sound higher up the piano, or lower down

to the depths, depending upon what he heard and what he felt needed to

be developed. He listened, and relating the sound to you, asked you to

expand the sound in volume or pitch according to what he heard. For the

pupil it was an extraordinary experience of discovery, of finding and

hearing a new self, a new ability to express a new life within.

In the 1930s he wrote his first

manuscript Orpheus or the Way to a Mask. He based the

title of the book on the story of Orpheus who had to descend into Hades,

the underworld, to find his lost wife, his anima figure, his voice. And,

like Orpheus, Wolfsohn says, we all have to descend into the depths of

ourselves before we can ascend into the heights. Until one has experienced

and recognised these depths it is difficult to reach the heights.

This applies literally when working

with the voice, the lower you go the easier it is to reach the higher

registers. And in the lives of many artists how many artistic works have

arisen out of the depths of despair into the light of creation. Wolfsohn

had experienced death, he had descended into the depths of despair and

he now had to become familiar with life. He realised that what matters

is not whether life loves us, but that we love life and are able to express

that love.

I must explain to you why the book

is entitled “… or the Way to a Mask”. At one time he

had seen photographs of Death Masks made on people who had died. He found

that, quote: “in this moment of our crossing the borderland between

life and death there must occur a final and absolute process of concentration.”

His sculptor friend wanted to make a mask of his face, so he decided he

must concentrate while it was being made so he sang and imagined music

all the time. When the mask was removed, to his astonishment he could

not recognise the face of the mask. After studying it for days he realised

that it was the face of him as a young boy in a photograph he had carried

around for years as a sort of talisman; he felt he had found his child

side again at last, and quote: “ I had reached part of the way I

had to accomplish, the part which said ‘Know thyself’ the

other part was governed by the imperative ‘Love thy neighbour as

thyself’. The way of knowing is to look. The way of loving is to

act”

In his Orpheus MS Wolfsohn examines and analyses mans vast creativity.

He was fascinated by dream. He believed that dream comes out of the wisdom

of the deepest unconscious without censorship of consciousness.

Through the millennium of time everything that man has created has emerged

from his creative unconscious, his dream centre, and is a manifestation

of the creator’s unconscious dream, whether he be an artist, scientist,

musician or writer. The fairy story of the flying carpet became the aeroplane.

In the 15th century Leonardo da Vinci drew a helicopter and a diving bell.

Scientists admit that they have solved equations during the night. Ingmar

Bergman, the Swedish film maker has said that all his films were from

his dream-source within. For many years authors have written realistically

about landing on the moon. So in many ways science is catching up with

science fiction.

In the 1930s there was a new art-form

– the film. He was very excited by it. He felt

it gave the filmmaker unlimited scope for portraying all his artistry

– he can use music, voice, fast change of scenery - but best of

all he can use montage, the magical change from one action to another,

often superimposed over each other as it is in our dreams. He felt that

film, using montage, the natural phenomena of dream, holds an important

advantage over theatre or opera.

Wolfsohn believed: I quote “The film has created a union between

the realm of what we call art with the realm of what we call life. Seen

as its’ own reality, art represents the soul held in suspended animation

and lacks the flowing movement of life. The film unifies the flowing movement

of life with the quiescence of art”.

I want to refer again to the painting

in Life? or Theatre? which we saw earlier. (4175) The movement of her

mother’s body depicts a sort of montage which Charlotte often uses.

I wonder if Wolfsohn would feel that here in her art, life does flow?

His concepts relating to dream

finally lead him to investigate his ideas about Man’s biggest

dream of all – the story of God’s creation of the world. The

solution of this ended his search for his own God. He came to the conclusion

that man has projected onto God an image of his own unconscious creative

possibilities - and man will finally create life out of matter, fulfilling

man’s image of God – and we are not all that short of this.

So, he believed that God is the deep creative source within each one of

us, a source which we need to nurture, to contact and allow freedom of

creative expression.

He felt that this freedom of expression

is as important in all forms of art as in voice. After all Art is the

voice of the artist. In Orpheus he speaks over and over again about various

artists and their work. So when he worked with Lotte and with her art

student friend, Marianne, he tried to encourage them to express their

inner dream in their paintings and to understand the resulting creation

in relation to their soul or psyche. He gave his Orpheus to Lotte to read

and the way in which she quotes him almost verbatim in Life? or Theatre?

is quite extraordinary.

As things were getting more and more dangerous for Jewish people in Germany,

Wolfsohn left for England in 1939. His mother had died

and, to his great grief, his beloved sister would not go with him. She

died later in 1943 in Concentration Camp.

In England he enlisted for the

British Army and fought once again in France, this time against Germany.

Here we see him playing chess with his comrades, a game he really enjoyed.

All his life, he played patience and read detective stories as a relief

from his serious thinking.

He was invalided out of the army

in 1941 and eventually he started to work with young voices in England.

In 1946 Marianne wrote to him saying that she had heard that he was alive

and would very much like to hear from him – but in view of the war

she would understand if he did not want to reply. He replied and their

correspondence became the beginning of his second MS – The

Bridge – a bridge back to Germany. He knew about Lotte’s

death but knew nothing about Life? or Theatre?. As he felt that Marianne

and Lotte were soul-sisters, in order to help Marianne understand herself

- he wrote extensively about Lotte, analysing her personality, her dreams

and her paintings.

So in the relationship between

Lotte and Wolfsohn we are extremely fortunate to have three records of

this era. Written in the order of their creation they are:

1. Wolfsohn’s manuscript Orpheus or The Way to a Mask

2. Charlotte’s Life? or Theatre?

3. Wolfsohn’s second manuscript The Bridge.

In Life? or Theatre? Lotte paints

the moment, she gives Daberlohn two paintings: “The Meadow with

the Yellow buttercups” and “Death and the Maiden”. She

says he can have one. He chooses the Buttercups but says he would like

Death and the Maiden as well because “That’s the two of us”.

She says he can borrow it

.

In his correspondence with Marianne he says of Lotte, quote: “She

was extraordinarily taciturn, quite unable to break through and emerge

from the barrier she had built around herself. I felt compelled to attack

this barrier but when I talked to her, trying to break it down, she would

gaze at me with such a challenging look which spurred me on to even greater

activity, forcing me to play the clown…..I always felt I had to

bring her closer to reality, there was such an air of unreality about

her”.

After describing how difficult

he found Lotte, Wolfsohn speaks of his Saviour Complex and his need to

help people. He asks the question: “whatever induces me to play

this ridiculous role? What forces me to go on talking in a never ending

torrent of words? What makes me speak about every deep realisation of

myself? Only because I want to help a little? – a bit embarrassing

isn’t it?”

He goes on to say “I comfort

myself with the thought of my favourite Michelangelo painting, God the

Father breathing soul into Adam. Here a similar process occurs - God must

perhaps consider himself lucky if Adam accepts his present…”

He believed that this painting was one of the most profound. Quote: “The

process of animation through the gesture of God’s arm is strikingly

meaningful. To touch means to move, to set in motion so that life can

be created. It is occurring in all forms of contact – the words

of the poet touch the composer, who writes the music for a song, this

in turn touches the singer, whose voice moves the audience. And the greatest

act of touching is the human act of love-making where new life is created”.

Discussing this brings me to the

frequently asked question “did they really have a love affair?”

The answer is we shall never know, but whether they made love or not,

she understood what he meant by this being the greatest and most important

contact between people.To underline this

(4875), in a series of paintings she depicts herself, with a shaven masculine

head quoting Wolfsohn’s ideas, using his very words to encourage

her grandmother to have faith in herself and find some creative outlet

for her emotions.Here (4889) and in at least

seven paintings she depicts herself in the same position as she depicts

Wolfsohn making love to her. I am certain that this was not a Lesbian

act, it is her way of depicting contact, of showing touch, hoping to that

her grandmother would give birth to come creative work. It shows once

again how much she fully understood his ides.

In The Bridge, Wolfsohn writes

about several of Charlotte’s paintings made while they were still

in Berlin. I would like to show two of them to you and give his analysis

of her through her art. Here is Death and the Maiden:

He believes it was the first drawing

he saw of hers, the one which urged him to help her in her struggle. He

says: “Out of the painting a great longing, a cry breaks out, a

yearning for an embrace, even with death……..a wish for someone

to put his arms about you…..Who would have thought that death can

be so human? Look at him! It is not true that a horri¬fying skeleton

grins at us, no human being of flesh and blood can smile so lovingly,

drawing us close”. Charlotte would have read this in Orpheus.

Later in The Bridge, he adds: “It is not without significance that

Death’s hand is on the girls head. In this head darkness had reigned..…wild,

restless demons from the depth had fought and clashed. In this head were

the mercilessly observant eyes of a painter’s soul….eyes forced

to discover the cruelty in the lack of understanding of the outer world

for her inner world….eyes whose soul-vision became blurred by watching

the clash between the world of ugly outer reality and that of inner dream

beauty…look at the shining expression of the Maiden’s eyes,

they glow and their glow relates directly with the right hand of Death

which rests on her shoulder. What warmth this hand radiates! … and

her eyes, what questions they ask! Will you heal me? Will you understand

me? Are you my Saviour? Can I at least trust you? These unanswered questions

dominate the picture”

After Death and the Maiden, he

told Charlotte she had come to the end of a particular road and she should

now portray the theme from another angle, the girl’s embrace with

life not with death. One day, without saying a word, she handed him a

drawing. He was quite shocked when he saw The Embrace (as

shown above. It is unfortunate but I cannot remove the striations! PS).

It represented a side of her that he did not know. Its passion

and earthliness was not what he had expected. He was fascinated by the

strength of expression, the firmness of line, the passion of movement.

Quote “Whereas Death and the Maiden showed a lack of sensuality,

the blending of figures into each other, no earthliness, only chastity

and nobility of expression, The Embrace is the entwining of bodies, a

strong earthliness, unrestrained abandonment and a predominant sensuality,

with almost an element of lust. I am sure she had no actual experience

of this as she had little to do with men and was much closer to women,

but her artistic gift did not need the experience of reality to be able

to portray abandonment, even to such an intense and realistic degree”-

end of quote. He saw this drawing as a continuation of the first, not

as the other side – and he felt one wall of rubber may have given

way.

Later in The Bridge he writes most

movingly: “Now whenever I look at Death and the Maiden there appears

before me Lotte’s real encounter with Death in the gas chambers

of Auschwitz, behind the door stands a very different Death from that

of her portrayal”.

He knew nothing about Life? or

Theatre? until in 1961 when Paula Lindberg-Salomon

sent him a brochure of the first exhibition of Lotte’s work. He

was completely devastated to see paintings of himself with her and to

realise how much he had in fact misunderstood the impression he had made

on her. He was deep in thought for two days.

In 1958 Wolfsohn became seriously

ill with tuberculosis and was admitted to Hospital. He was completely

cured and after a long convalescence, returned to work. In 1962 he was

again admitted to hospital to have a kidney stone operation. He contracted

the deadly hospital staphylococcal disease, now known as MRSA, and died

before the operation could be performed.

From 1945 to his death in 1962 he proved that his ideas about the voice

could be brought to fruition, a phenomena demonstrated by many of his

pupils. However, with concepts about the voice and the human being so

basically grounded in tradition, it was difficult to gain real recognition

in either the musical or psychological worlds in his lifetime, his ideas

were too far seeing and too challenging.

After his death, Roy Hart,

his most accomplished pupil, formed the Roy Hart Theatre which moved to

Malerargues in France in 1975. The Theatre is still very much alive and

has recently held a Seminar on the Legacy of Alfred Wolfsohn.

The legacy points out that his ideas might well have died with him but

for two people: Charlotte Salomon and Roy Hart. Alfred Wolfsohn continues

to live both in Charlotte’s Life? or Theatre? and in the Roy Hart

Theatre. It is interesting that the word “theatre” occurs

in both these titles and although Wolfsohn did not speak a great deal

about theatre, on hearing about a strange occurrence or someone’s

outrageous behaviour he would often laugh and say, “Life is stranger

than Theatre”.

Was Charlotte in fact echoing

his words in the way she writes Life? or Theatre?

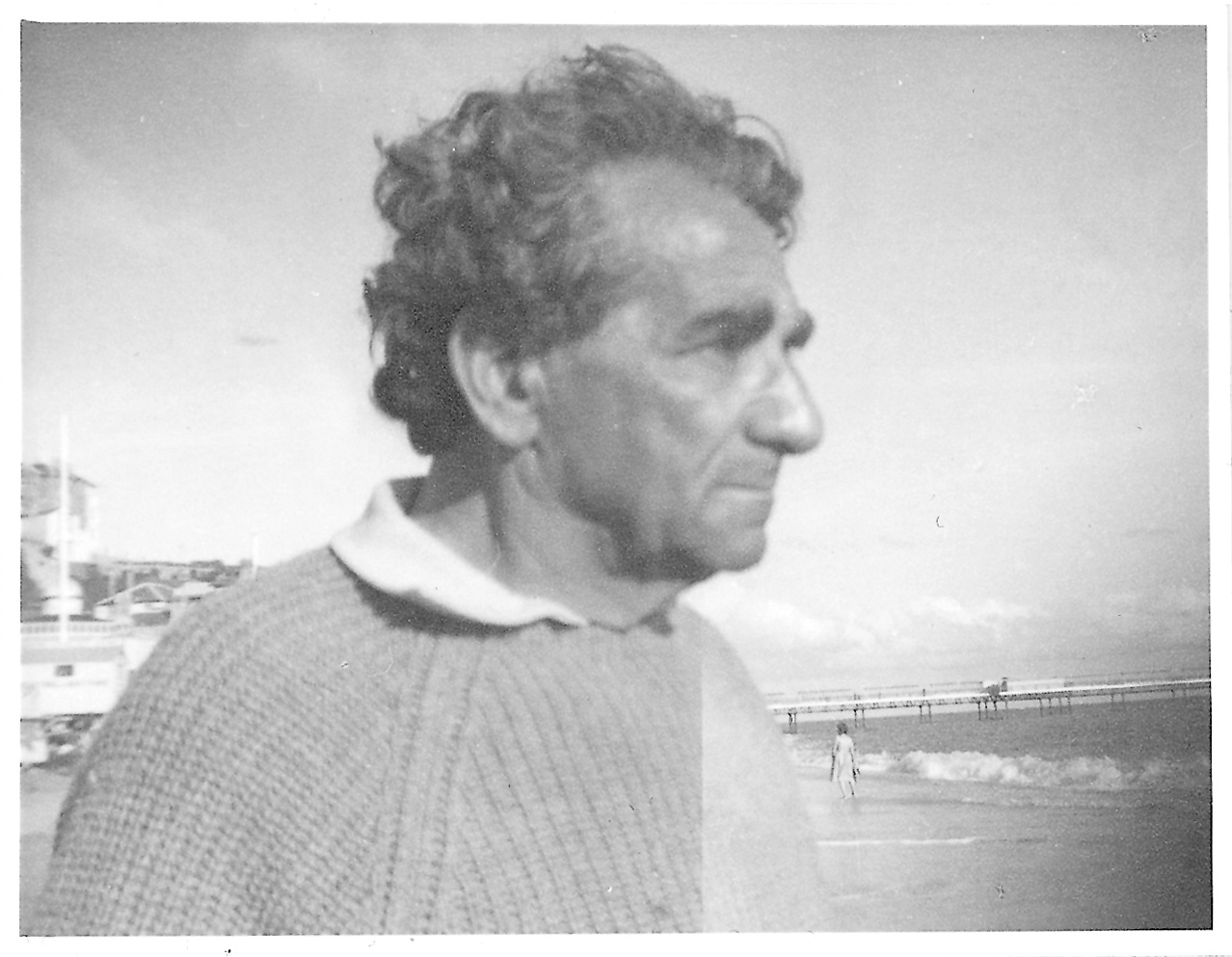

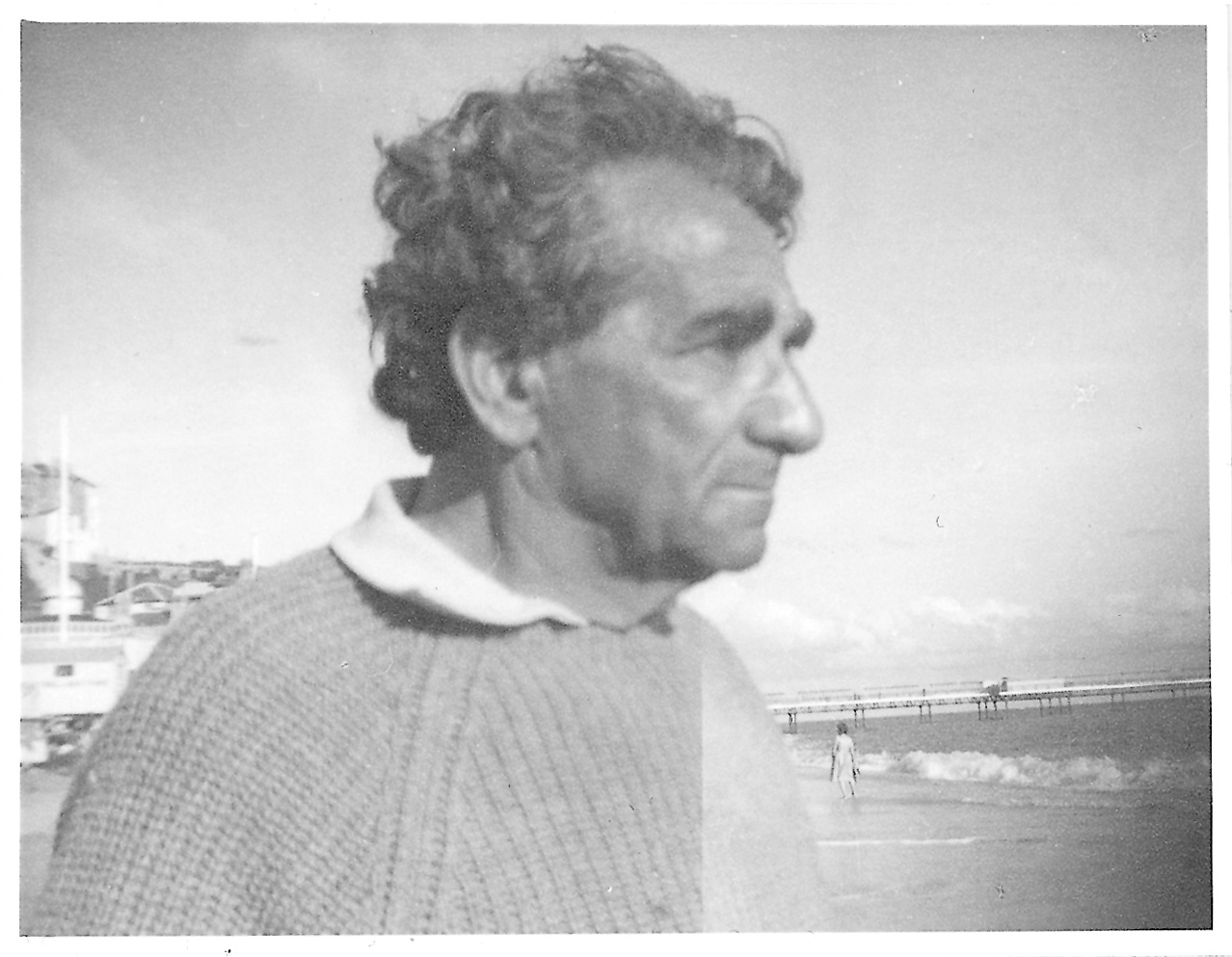

To finish I would like to show

you a photo:

This, taken by the sea a short

time before he died: In his dream about death, Wolfsohn asked his God

to make him into a fermata – so that he would remain

an everlasting sound placed on the horizon between the sea and the sky.

Here he is looking out in his concentrated way towards this horizon. And

this leads in the end to the Nietzsche quotation which he felt epitomised

his whole philosophy “Lerne singen, o seele”. Learn to sing,

oh my soul.

And finally (4744) Charlotte’s

prophetic painting – exactly what is happening here today.

“One day people will be looking at the two of us”.

REFERENCES .

1. All copies of the work of Charlotte Salomon from the Collection Jewish

Historic Museum, Amsterdam. Copyright Charlotte Salomon.

2. All excerpts and quotations from Orpheus or the Way to a Mask and from

The Bridge, from the Alfred Wolfsohn Collection, Jewish Museum Berlin.

3. All photographs of Alfred Wolfsohn or his pupils and sound recordings,

from the “Roy Hart Theatre Association” (Archives) www.roy-hart.com

4. The Audio excerpts from the CD “Alfred Wolfsohn – his musical

ideas”, from the “Roy Hart Theatre Association” (Archives)

www.roy-hart.com

Sheila Braggins

- Reponses to Sheila's

lecture -

Sheila

Braggins spoke very eloquently

in her lecture, to quote a Dutch member of Roy Hart

Theatre who was there that afternoon, Maurice “I

was so touched by this lecture of the English woman. She gave a very inspiring

lecture. I loved her because she was so lovely and unconventional. Young

in hart and spirit.”

Sheila really did reach

out to her audience that day and here is another account of from a long

time student and friend of the late Marita Gunther, Zwaantje de

Vries:

Dear friends,

Time goes fast as everyone knows but the 16th September 2007, will be

one of these days that will be hard for me to forget - and I am sure,

not only for me.

For the Jewish Historical Museum

in Amsterdam, that day was the last day of the Charlotte

Salomon exhibition “Work in Progress”.

For the Roy Hart Theatre, that day was the first day

that the story of Charlotte Salomon and Alfred Wolfsohn was given a voice.

For me, that day was a day of reconnecting again, of

realising how deeply rooted the work of Charlotte and Wolfsohn is in me

and how it has affected my life.

This is why I would like to

share my experience with you, readers of the Archives website.

It will be a personal sharing, because I know that all of you are familiar

with the “Story” of Charlotte, Wolfsohn and the RHT.

As I was lucky enough to have

been Marita Gunther’s pupil and close friend for years, Sheila's

lecture did not give me any information on Wolfsohn that I hadn’t

already heard. But on this special day, I was very impressed by seeing,

hearing and feeling his spirit through Sheila. Marita often told me about

her but we had never met. Seeing Sheila, was almost seeing Marita again.

I could fully understand why these two women had a very special bond.

Sheila gave voice to Charlotte's

story in paintings but the way she directed the lecture was giving voice

to so much more than just that story.

In her voice, the power of creativity resonated. That power that made

the work of Charlotte and Wolfsohn live on after their deaths. It was

death itself that contained the source of that creativity. Everyone who

has been in contact with Charlotte’s work can see what that means.

As can everyone who has been lucky enough to have had singing-lessons

with the student/friends who were close to Alfred Wolfsohn. During the

years that Marita Günther was my singing teacher and close friend,

I came to understand that her life was deeply connected to the spirit

of Alfred Wolfsohn.

Before I met the RHT, I had

discovered Charlotte's work. It was in the 1970’s at the first big

exhibition of her work in Amsterdam. My sister, Vera, and I went there.

I cannot describe the shock it gave us. The only answer we had was to

cry and we were not the only ones.

Something moved us very deeply but that was not all. Since both of us

were painters, we realised through her work that art can be personal and

subjective. That fact in itself was already amazing because at that time

one was supposed to paint wildly and abstract with no relation to ones

own soul and that was not the story we wanted and needed to tell.

Much later I realised that our shock must have had everything to do with

an awareness of death.

At the time, we were not yet conscious of its devastating influence on

our youth and our own war-traumatised parents.

But what we did know after seeing Charlotte’s work was that creativity,

art, theatre and music were the tools we needed to survive - and much

later also to heal. So one could say, we dedicated our lives to, in fact,

'Leben? oder theater?'

And although my sister and I

went different ways, Charlotte's book was and is for us both like an anchor

in our development. If life is hard or my expression lacks inspiration,

turning the pages of Charlotte’s book always gives consolation .

“Yes, art is life: my life and your life.”

Some years later, Vera, R'dwan,

Iara and I went to Alès in the South of France and were participants

in one of the first RHT Workshops. Diana Palmer and Robert Harvey opened

the doors to my singing voice.

This first workshop gave me

the same quality of shock, My expression was mine and did not need to

fit into a model or school. My singing voice was emerging from a place

where I was me, myself.

Frightening. I needed time to fully comprehend the idea that there was

no way back. Or actually, no way to try and get away from that source.

More and more towards me. That was the only choice left for me to move

on my way.

Sheila on that day personified

these spirits for me as she spoke of Wolfsohn and Charlotte.

Through her I could reconnect again with Marita, and also with these first

meetings with the theatre.

'Life or Theatre' was breathing in every cell of the RHT in those days.

It was the way of being dedicated to life, to the other, to the quality

of interaction in the daily routines and its condensation in the singing

lessons that brought the spirits of Charlotte Salomon, Alfred Wolfsohn

and Roy Hart into my life - and into the lives of others.

I personally miss this sometimes.

It is not easy to feed oneself without the support of others.

And one day, suddenly there

is a mail from Clara and Paul, telling me that there will be a lecture

on Wolfsohn and Charlotte in Amsterdam. All at once I am awake, as if

home is calling “There is a party and you are invited to this special

occasion.!”

So it came that I could witness others hearing this important story of

how Alfred Wolfsohn and Charlotte Salomon came to the inevitable choice

to do the work they did.

I hope that you, dear friends,

realise how important it is to keep telling about the source of the work.

I am convinced that there is a need for that in the world.

And it is a big shame that Alfred Wolfsohn, his pupils, his work and the

RHT, still are so unknown.

I am very happy to have been

to the lecture, and having had a good time with Clara, Paul and Sheila

afterwards. For me our circle felt larger than the four persons at that

table in an Amsterdam restaurant. The circle included those who couldn't

be there and those who left us to other dimensions.

That is why I felt reconnected again with that spiritual family of creativity.

That is why it felt like coming home..

Thank you for

being there!

Clara, Paul and Sheila, thank you for the 16th September!

Love from

Zwaantje de Vries

Zwaantje

(far right) and Maurice (second row, centre) with Iara and Rdwan, the

first arrivals at the lecture

Alfred

Wolfsohn home page

Writings

about Alfred Wolfsohn index page

Website

home page